Trissino, Giovan Giorgio

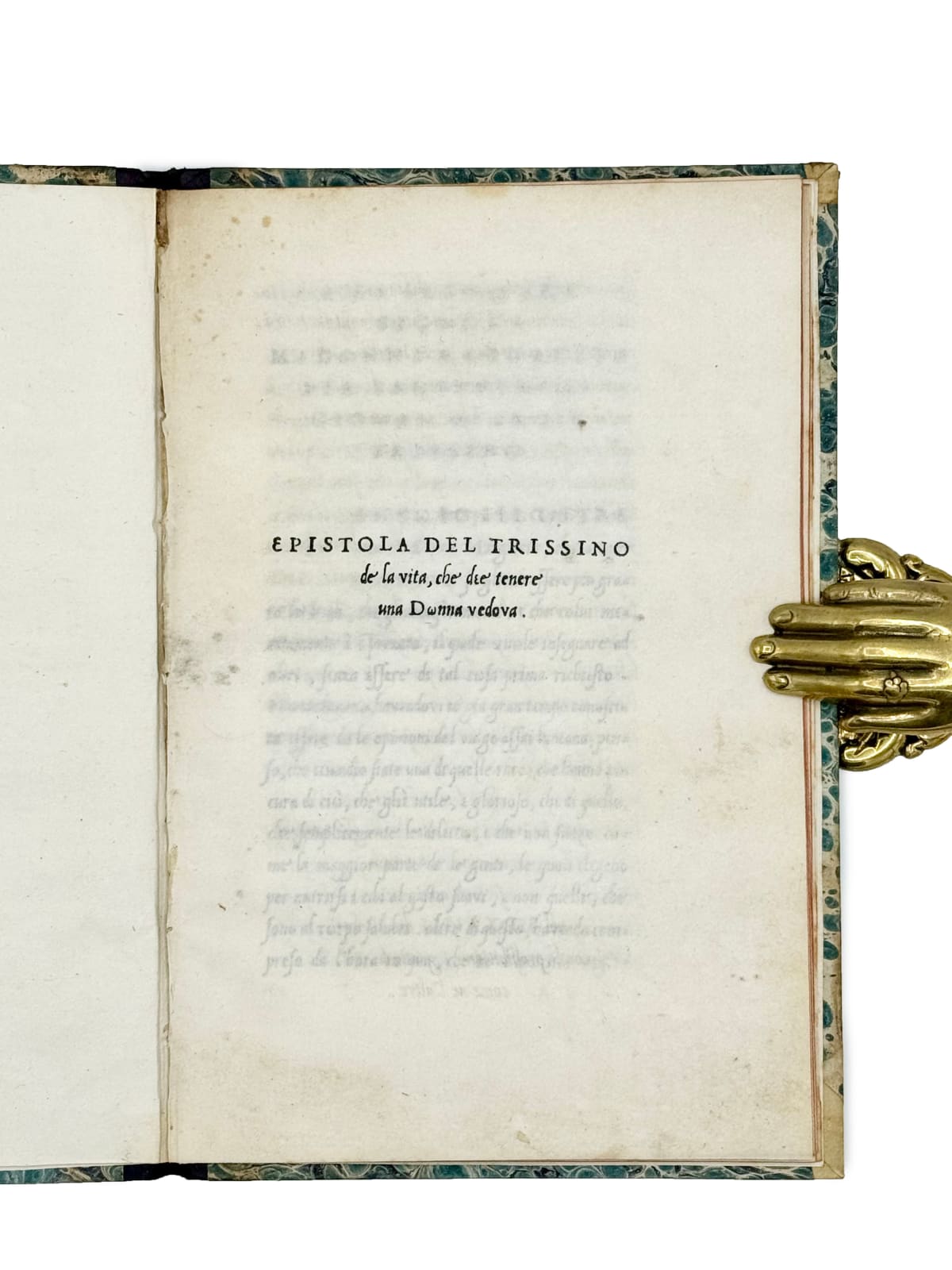

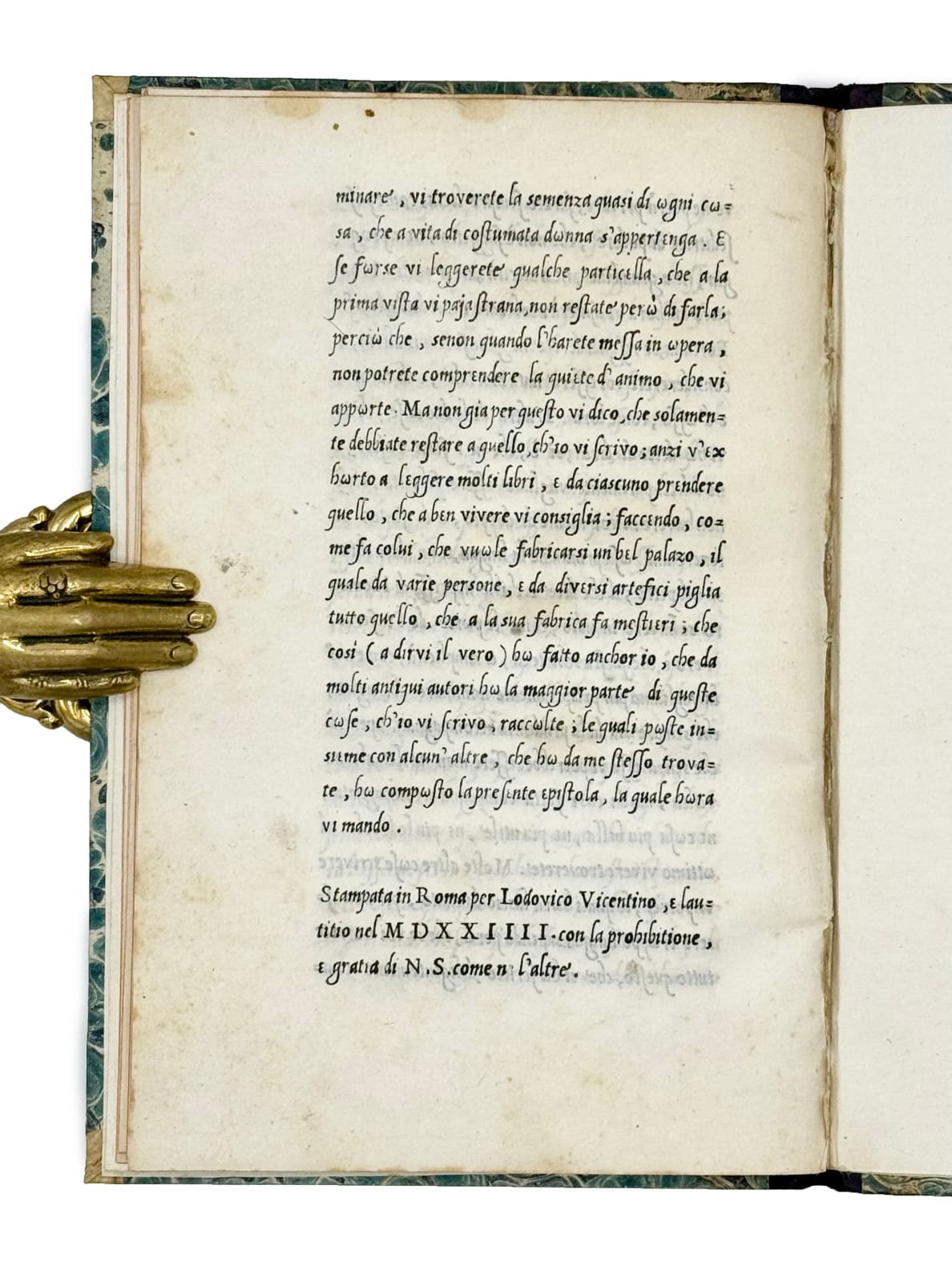

Epistola del Trissino de la vita, che dee tenere una donna vedova, 1524. Rome. Lodovico vicentino and Lautitio.

Humanist Renaissance advice for widows on how to behave

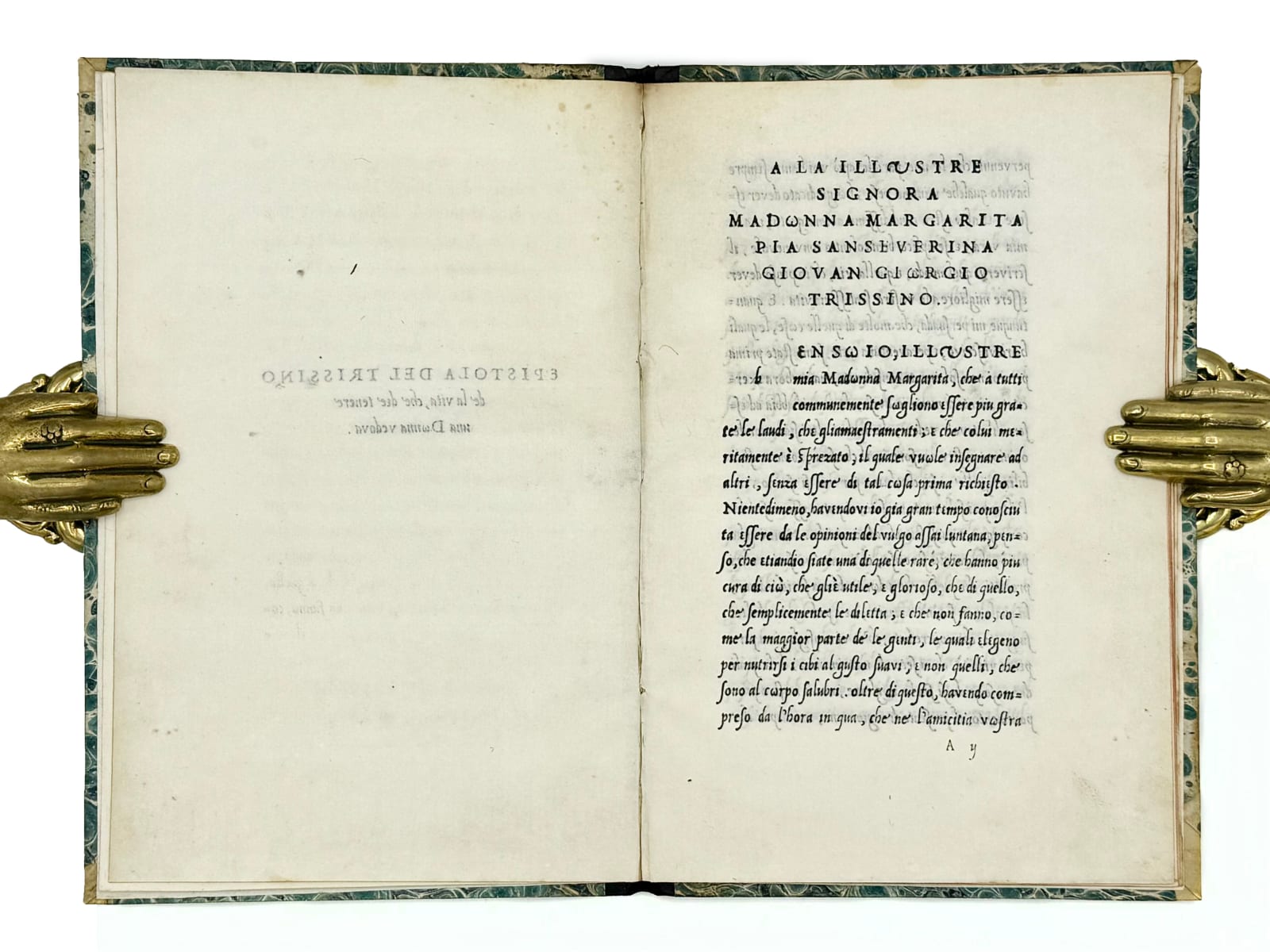

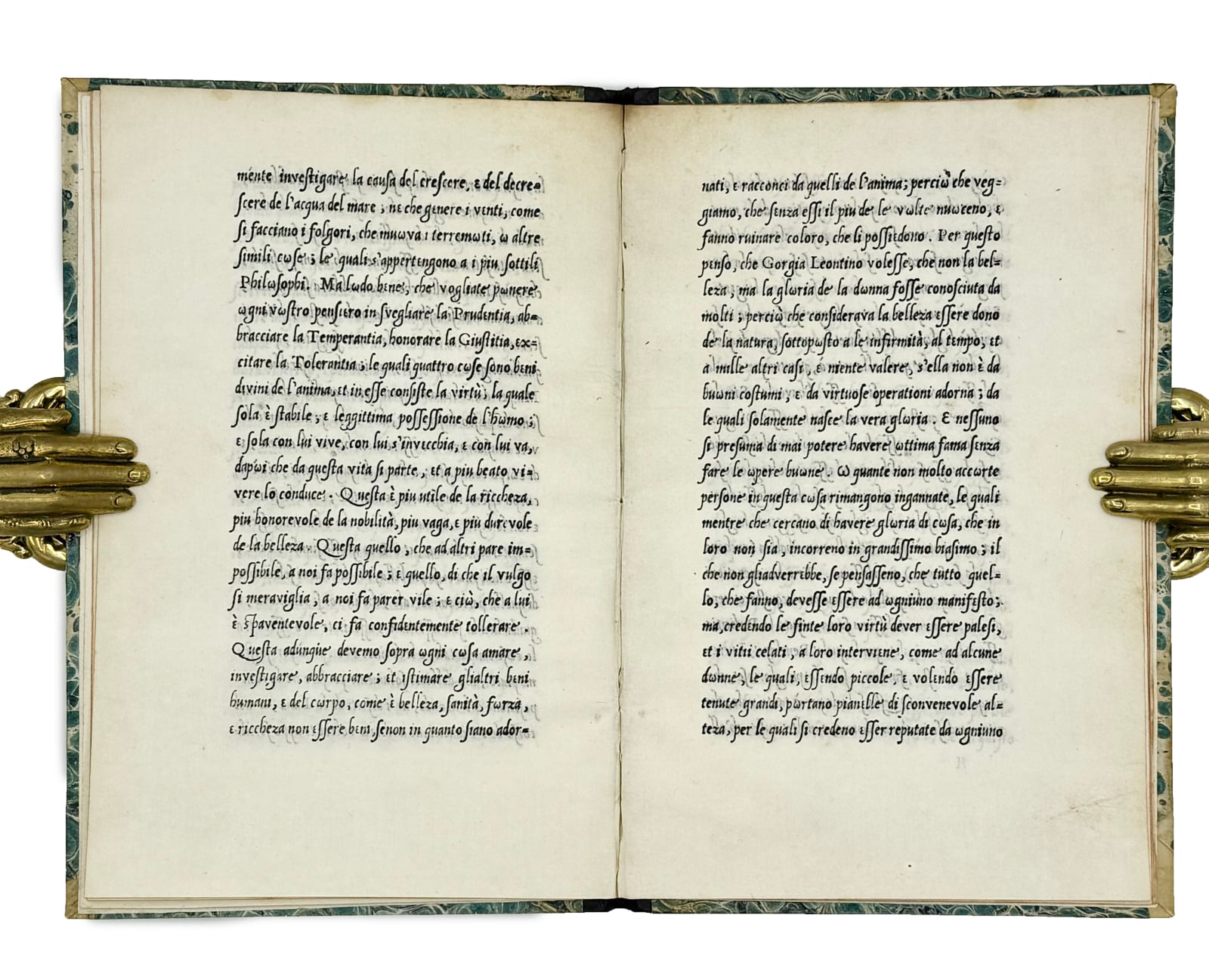

Extremely rare first edition of this brief pedagogical treatise written in epistolary form, addressed to noblewoman Margherita Pio Sanseverino, offering an intellectual humanist perspective over the strict rules on female behavior dictated by Savonarola. Printed with the beautiful chancery Italic types by Trissino, which brought forward his ideas on the orthography of the Italian language proposing a reform with new characters inspired by phonetic principles.

Extremely rare first edition of this brief pedagogical treatise written in epistolary form, addressed to noblewoman Margherita Pio Sanseverino, offering an intellectual humanist perspective over the strict rules on female behavior dictated by Savonarola. Printed with the beautiful chancery Italic types by Trissino, which brought forward his ideas on the orthography of the Italian language proposing a reform with new characters inspired by phonetic principles.

$ 9,000.00

Further images

8vo. 12 ff. Elegant 20th century half-calf, marbled covers, gilt title and fillets to spine.

“If Savonarola’s treatise largely conjured up the image of a widow who lived like a secular nun, a more permissive tone was produced in the treatise by Giovanni Giorgio Trissino of Vicenza... Trissino began by stressing the widow’s rights and her spiritual equality with males as a woman. He spoke of her as a free woman ‘who is not subject to a husband, a father or any other man’. And he encouraged her with the thought that she was born, like all humans, as a man in soul, and just happened to have been placed in a female body... Like his predecessors, Trissino offered the widow the life of privacy in her household and virtuous behaviour, educating her children and guarding their inheritance... Trissino forbade the widow to discuss war or affairs of state and warned her not to reveal her innermost thoughts, nor speak impulsively without thinking. She was to be approachable, rather than arrogant, and needed to avoid being argumentative and difficult to please...” (King).

The volume is among the first rare works printed by Trissino in Lodovico de gli Arrighi’s Roman workshop, featuring the elegant Italic type finely cut by Lautizio di Bartolomeo dei Rotelli, a goldsmith from Perugia. The collaboration between Trissino and Arrighi marked a pivotal moment in the history of lan- guage, of print and in the contemporary literary debate; this was apparent even to Trissino himself, who highly valued Arrighi’s contribution not only in putting to print some of his linguistics reforms, but also in doing so in a most remarkable way by designing a splendid Italic with punches carved like works of art, which perfectly showcased his talent as calligrapher. He himself will say of Arrighi: “His miracle is in having found this beautiful way of doing with print almost everything that he previously did with the pen.”

Gamba 1703 (mention). Breman 4. D. Romei, Catalogo abbreviato delle edizioni tipogra- fiche di Ludovico degli Arrighi detto il Vicentino (1524-1527), p. 8. Morsolin, p. XXXVII. C. King, Renaissance women patrons: wives and widows in Italy c.1300-c.1550, p. 34 and ss.

“If Savonarola’s treatise largely conjured up the image of a widow who lived like a secular nun, a more permissive tone was produced in the treatise by Giovanni Giorgio Trissino of Vicenza... Trissino began by stressing the widow’s rights and her spiritual equality with males as a woman. He spoke of her as a free woman ‘who is not subject to a husband, a father or any other man’. And he encouraged her with the thought that she was born, like all humans, as a man in soul, and just happened to have been placed in a female body... Like his predecessors, Trissino offered the widow the life of privacy in her household and virtuous behaviour, educating her children and guarding their inheritance... Trissino forbade the widow to discuss war or affairs of state and warned her not to reveal her innermost thoughts, nor speak impulsively without thinking. She was to be approachable, rather than arrogant, and needed to avoid being argumentative and difficult to please...” (King).

The volume is among the first rare works printed by Trissino in Lodovico de gli Arrighi’s Roman workshop, featuring the elegant Italic type finely cut by Lautizio di Bartolomeo dei Rotelli, a goldsmith from Perugia. The collaboration between Trissino and Arrighi marked a pivotal moment in the history of lan- guage, of print and in the contemporary literary debate; this was apparent even to Trissino himself, who highly valued Arrighi’s contribution not only in putting to print some of his linguistics reforms, but also in doing so in a most remarkable way by designing a splendid Italic with punches carved like works of art, which perfectly showcased his talent as calligrapher. He himself will say of Arrighi: “His miracle is in having found this beautiful way of doing with print almost everything that he previously did with the pen.”

Gamba 1703 (mention). Breman 4. D. Romei, Catalogo abbreviato delle edizioni tipogra- fiche di Ludovico degli Arrighi detto il Vicentino (1524-1527), p. 8. Morsolin, p. XXXVII. C. King, Renaissance women patrons: wives and widows in Italy c.1300-c.1550, p. 34 and ss.

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.