![Sir John Mandeville, Itinerarium [in Italian] Tractato de le piu maravegliose cosse, [c. 1496- 1499]. Florence. [Lorenzo Morgiani].](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_1600,h_1600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/hsrarebooks/images/view/a657b3900e4a56f07ab04490719450ebj/hsrarebooks-sir-john-mandeville-itinerarium-in-italian-tractato-de-le-piu-maravegliose-cosse-c.-1496-1499-.-florence.-lorenzo-morgiani-..jpg)

![Sir John Mandeville, Itinerarium [in Italian] Tractato de le piu maravegliose cosse, [c. 1496- 1499]. Florence. [Lorenzo Morgiani].](https://static-assets.artlogic.net/w_1600,h_1600,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/hsrarebooks/images/view/690618b71fa4c08e97e4a92c2cdb244ej/hsrarebooks-sir-john-mandeville-itinerarium-in-italian-tractato-de-le-piu-maravegliose-cosse-c.-1496-1499-.-florence.-lorenzo-morgiani-..jpg)

Sir John Mandeville

An Italian vernacular edition of the Travels of Sir John Mandeville, the fundamental travel book, first best-seller in the genre, and a text which greatly influenced the course of subsequent exploration. One of the most popular texts of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, taking the reader to the Holy Land, Egypt, Turkey, Persia, Tartary, India and Cathay, its influence was profound and persisted well into the era of printing and the age that saw the Western discoveries of the New World and the sea routes to Asia.

Small quarto, (198 x 130 mm). 80 ff., text printed in roman letter in double columns. Bound in 19th century red morocco, by Bedford, raised bands to spine, finely tooled and lettered in gilt. Lightly washed, traces of dust-soiling to title, one minute wormhole, a few marginal tears repaired, but an excellent copy.

In 1625 Samuel Purchas thought Mandeville ‘was the greatest Asian Traveller that ever the World had’, next – ‘if next’ – to Marco Polo (Pilgrimes III/i p. 65). Even if we can doubt the absolute truth of Mandeville’s narrative today – and there are arguments for and against – it has never been out of print in one form or another, and together with Marco Polo’s narrative it encapsulates for us a medieval world-view finally succumbing to a “modern” traveller.

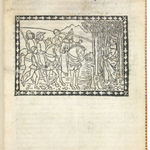

The illustration is composed of a woodcut on title portraying a group of riders meeting Mandeville (with book in hand) by the entrance to a wood; 3 woodcut printer’s marks.

‘When Leonardo da Vinci moved from Milan in 1499, the inventory of his books included a number on natural history, the sphere, the heavens – indicators of some of the prime interests of that unparalleled mind. But out of the multitude of travel accounts that Leonardo could have had, in MS or from the new printing presses, there is only the one: Mandeville’s Travels. At about the same time... Columbus was perusing Mandeville for information on China preparatory to his voyage; and in 1576 a copy of the Travels was with Frobisher as he lay off Baffin Bay. The huge number of people who relied on the Travels for hard, practical geographical information in the two centuries after the book first appeared demands that we give it serious attention if we want to understand the mental picture of the world of the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance’ (C. Moseley, ed., The Travels of Sir John Mandeville, 1983, p. 9).

Of great significance is the book’s discussion of the notion that the globe can be circumnavigated (it is often said that the reading of Mandeville gave Columbus the idea of sailing to the west to reach the east). Although Mandeville continues to present the east as exotically different, and continues the exciting myth of distant realms populated by monsters and strange human forms, his discussion of the physical and geographical “proof” of the size and shape of the earth also serves to bring the east – together with the Antipodes – into the discoverable and real world.

Originally written in French (quite possibly the Anglo-Norman still current in English court circles) the book first began to circulate in Europe between 1356 and 1366. By 1400 it was available in every major European language and by 1500 the number of manuscript copies was vast – indeed over 300 have survived, compared to only about 100 of Marco Polo. The early printed editions testify at once to the importance attached to the Travels and to its commercial appeal. All early editions are now of great rarity on the market, especially those, such as this, in the vernacular languages.

This is one of seven editions in Italian from incunable presses (first, Milan 1480). It has the extra attraction of a Florentine woodcut on the title-page depicting Mandeville himself, book in hand. The exceptional popularity of the Italian editions in the late fifteenth century is particularly striking ‘when we remember that not onlywas Columbus himself an Italian, but that north Italy was at that time the main centre of discussion of the western and eastern voyages. Mandeville’s information on Cathay was of importance to Columbus and probably Toscanelli before him; Cabot, Vespucci, and Behain all had connections with north Italy... It is notable that the decline of Italian maritime and commercial supremacy in the mid sixteenth century exactly coincides with the cessation of [Italian] editions’ (C. Moseley, ‘The availability of Mandeville’s Travels’, The Library XXX, 1975, p. 132). Other fifteenth-century editions were in Latin, English, French and German, the earliest apparently being in Dutch, circa 1470-77. ‘The listing of early editions of the Travels is very difficult, both because of the number of these editions in every major language of Europe, and because the surviving copies of this very popular little book are so very rare and widely scattered’ (Bennett p. 335).

Little is known of Sir John Mandeville himself. He tells us that he was an English knight, that he travelled from 1322 to 1356, and he served with the Sultan of Egypt and the Great Khan. Although very unusual, a journey at this time as far as China is not in itself improbable: the Franciscans, like Odoric of Pordenone or John of Plano de Carpini, and a few merchants, like the Polos and Balduci Pegolotti, reached the Far East during the period of Tartar hegemony (roughly the century after 1220) and lived to write their memoirs.

Mandeville may pose problems of authenticity for the modern historian, but there is no doubting the effect that his book had while it circulated in manuscript, once it was disseminated more widely in print, and indeed until the present day. It is a work that fired the global imagination. It helped to create a demand for a route to China and the Indies, and so served as both imaginative preparation and motive force for the explorations and discoveries of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

ISTC (im00176500) records just four copies, three in Italy –Florence (2) and Perugia (imperfect) – and another in the British Library. There is also a copy in Paris. Opinions have varied both as to the identity of the printer and the date; but it now seems most likely that it was printed by Lorenzo Morgiani between 1496 and 1499. On this subject, see the full report below by Dr. Martin Davies, whose help in identifying the printer and dating the edition we gratefully acknowledge.

Report by Martin Davies, Mandeville, Itinerarium:

Frank Isaac’s catalogue of British Museum books 1501-1520 assigns the printing of this book to Gianstefano di Carlo, working for Piero Pacini of Pescia, whose devices are found at the end. The BM Italian short-title catalogue (1958), p. 408, does not assign to a printer but gives the date as [1505?]; ISTC assigns to ‘[Gian Stephano di Carlo da Pavia?], for Piero Pacini, [about 1505]’. Gianstefano, however, is not recorded in a dated book before 1511, and of the books tentatively assigned to him by Isaac, the earliest is of October 1508. (footnote 1) More decisively, the type is not, as Isaac states, Gianstefano’s 87R, which he describes as having ‘i with a short stroke’, whereas the i in this book is dotted as normal; his facsimile of the type on p. 202 reveals other differences.

ISTC (im00176500) mentions the alternative, less preferred, assignation: ‘Also recorded as [Lorenzo Morgiani, about 1500]’, which derives from the assignation by IGI 6109 after examination of the Italian copies, and was accepted by Rhodes and the Gesamtkatalog. (footnote 2) And this seems to be nearer to the truth. The measurement of this type is consistently closer to 85 mm for 20 lines. It conforms in other respects, save one, to the discriminations listed in BMC VI 680 on Morgiani’s 85R type: ‘small round text type ... Separate Q with medium curved tail, irregular S, loop of e rather shallow, dotted i, [paragraph mark] of 81G. ... At first t isof normal length, with short head and medium curved foot; the place of this is taken, in the first book printed by Morgiani alone [i.e. not in partnership with J. Petri] (October, 1496, IA.27821) and after, by shorter, rather squat t with pointed head (see facsimile). A few undated books, one signed by the partners (IA.27952), shows an admixture of gothic 3 [i.e. a terminal m] ...’. The squat pointed-head t is found throughout the Mandeville (e.g. tutte, line 4 of the title-page), as are the irregular S, small-looped e, etc. The gothic m is occasionally found too (Item, i5v col. a line 12 from bottom, totum, k4r col. b line 4). When comparison is made with the similar type of Tubini (BMC VI 693), to whom GW first assigned the printing, it becomes apparent that the stroked h ‘with straight shanks’ of Tubini’s 86R is a distinction of that type from Morgiani’s 85R; and the sort here (commonly found in ch for che) does indeed have a rounded outer shank, gothic style. A further distinguishing mark seen in the BMC facsimile (Morgiani 85R, plate XLIX) but not mentioned in the text is that the third shank of m is, as it appears on the page, slightly but consistently detached from the two preceding, just as in the Mandeville type.

BMC’s entry for the signed and dated Morgiani & Petri edition of Mandeville (G.6705, VI 681-82, in gothic type, 7 June 1492) mentions the ‘title-cut (an emperor on horseback with four attendants confronted by a sage with a book on the edge of a wood)’ which ‘recurs on d4b of the 1498 edition (IA.28049) by the Compagnia del Drago’, another Florentine printing house, of the Fior di Virtù, without mentioning that it is the identical cut to that found in the present Mandeville in roman type. According to Sander (4174), the cut is in this book ‘un peu fatigué’ relative to its outing in 1492, but the fatigue is not obvious in comparing the two side by side (footnote 3).

The only difficulty in assigning the book to Morgiani, who is not known to have printed into the sixteenth century (BMC VI xviii), is that the Qu | here (with tail of medium length) is a single sort, not the separate Q|u of Morgiani’s 85R. But the appearance of the other distinguishing features of that type at the point when, for unknown reasons, Johannes Petri dropped out of the partnership, suggests that it is indeed his work, and of the fifteenth-century (Morgiani and Petri started printing for the Pescian publisher Pacini in 1495). He may have worked in collaboration with Tubini, say, whose closely resembling 86R does have such a Qu|, and who in turn was involved with the Compagnia del Drago. Further examination of all their work at the end of the 1490s may clear up the discrepancy. Another route would be to examine the state of the publisher’s devices of Piero Pacini. (footnote 4) For now, it seems most likely that the book was printed by Lorenzo Morgiani, c. 1496-99.

Copies are recorded in ISTC at London, British Library (G.6701); Firenze Accademia delle Belle Arti; Firenze Riccardiana; Perugia Comunale (imperfect) Another copy, not in ISTC or B. Jammes catalogue of the incunables there (1990), is in the Bibliothèque de l’Institut de France, Paris, according to the GW manuscript, confirmed by the Institut online catalogue as at 4°S 113 Réserve.

Footnotes:

1 F. Isaac, An Index to the Early Printed Books in the British Museum, Part II, MDI-MDXX, Italy, Switzerland, and Eastern Europe, London, 1938, no. 13486. F. J. Norton, Italian Printers 1501-1520, London, 1958, p. 29. More recently Adolfo Tura has sought to bring Gianstefano’s unsigned production back to as early as 1502: Edizioni fiorentine del Quattrocento e primo Cinquecento in Trivulziana, Milan, 2001, 33. He did not in any event print in the fifteenth century.

2 D. E. Rhodes, Gli annali tipografici fiorentini del XV secolo, Florence, 1988, no. 425; GW M20444 (M-numbers are those given in the manuscript of the GW online at www.gesamtkatalogderwiegendrucke.de/). The Bassenge sale catalogue, 14 April 2011, no. 1072 misunderstands the GW entry ‘[Antonio Tubini] für Piero Pacini [vielmehr Laurentius de Morgianis], [nach 1500(?)]’ to mean ‘Antonio Tubini für L. de Morgianis’, whereas it means ‘(more probably) [L. de Morgianis] for Piero Pacini’.

3 Neither Max Sander (Le livre à figures italien depuis 1467 jusqu'a 1530, 6 vols, Milan, 1942, nos 4169 and 4174) nor Paul

Kristeller, Early Florentine Woodcuts, London, 1897, 256a-b, reproduces the cut, but it is found in Rhodes, Annali, tav. XX, from the 1492 edition.

4 A Pacini book in the BnF (G. Dati’s Sfera) is reassigned from Morgiani & Petri c. 1495-1500 to Gianstefano di Carlo c. 1509 on the basis of ‘l’état des 3 marques’ in CIBN, I, p. 626.

GW, M20444; Howgego, ‘Encyclopedia of Exploration 1800 to 1850’, M39; IGI, 6109; Kristeller, 256b (title- page woodcut); Lach, ‘Asia in the Making of Europe’, I, pp. 77-80 and passim; Lowendahl, ‘China Illustrata Nova’, 2 (1480 edition); Not in Goff; Reichling, 1260. (104/516)

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.