Wadstrom, Carl Bernard

One of the most powerful broadsides in Anglo-American history, exceedingly influential, exploiting both text and image to demonstrate the barbarity of the trans-Atlantic slave trade.

Large broadside, 520 x 645 mm. Woodcut and letterpress, two sheets joined at middle, small piece of paper missing at top not causing loss, small closed tears not affecting either image nor text, creasing from fold, overall very good.

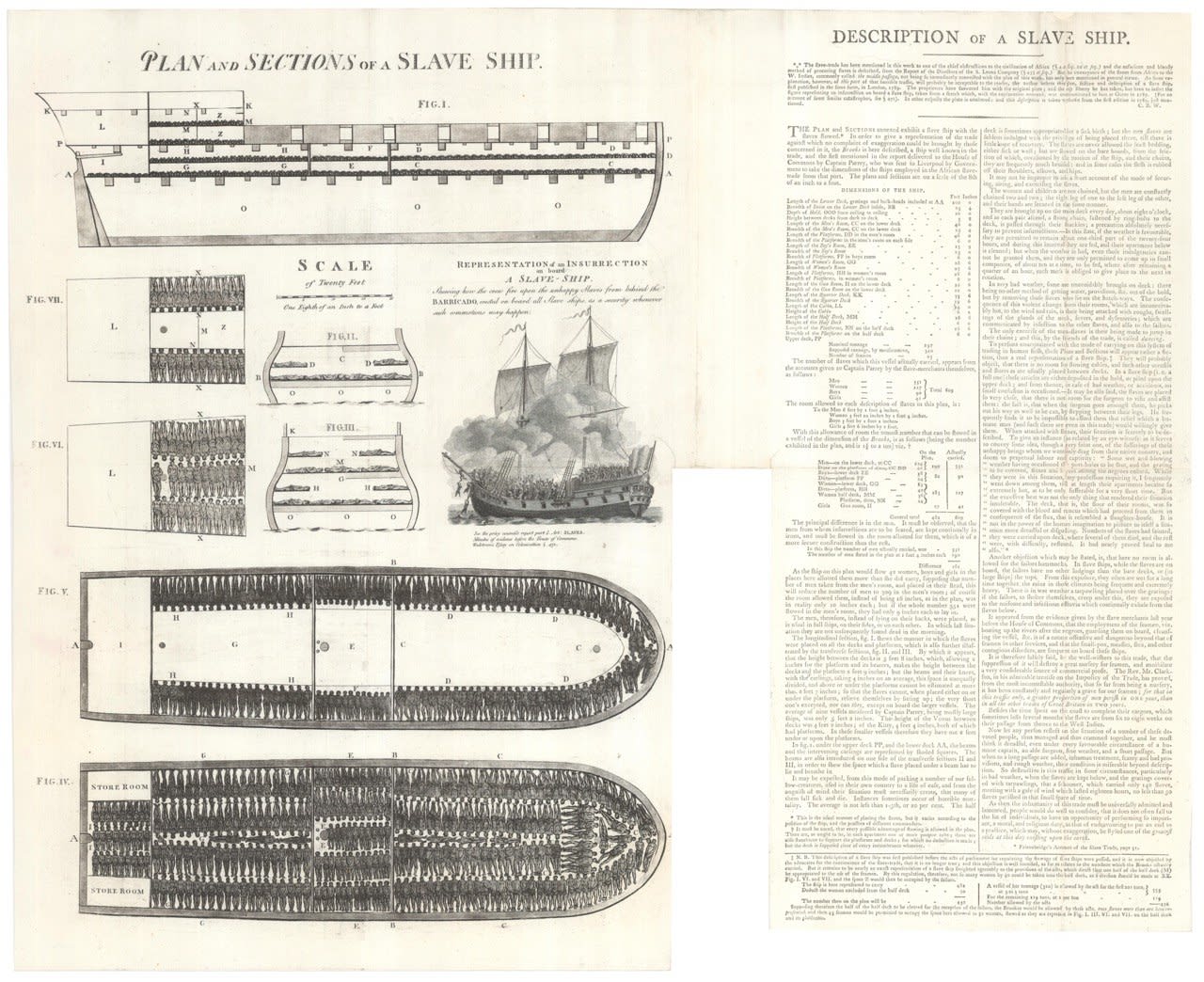

The present, large, engraving is a rare variant of the 1789 representation of the slave ship Brookes, and is here enhanced by a large vignette Representation of an Insurrection on board A Slave Ship. The broadside is divided in two parts, the right portion being the description of the slave ship, providing details on the dimensions of the decks and precarious and inhumane living conditions, and recounts the loss of life during the “Middle Passage”, based on Alexander’s Falconbridge’s account.

An example of one of the more potent images in the early days of the Abolitionist Movement. On the left are versions of Captain Parry's famous diagrams of how slavers 'stowed' the most slaves in a single ship, here augmented with a vignette, ''Representation of an Insurrection on board a Slave-Ship'', illustrating how the ship was defended. On the right is letterpress relating Parry's report to a House of Commons committee.

By the early 1780s there was a strong and growing abolitionist movement in Britain and America, notably among members of the Quaker community. The movement in Great Britain gained much momentum, though, when in 1787 a dozen men formed the non-denominational Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade. The group’s effectiveness was abetted by the inclusion of three Anglicans, including Thomas Clarkson (1760-1846) and Granville Sharp; by Clarkson’s own determination and genius for publicity; and by an alliance with MP William Wilberforce.

The Committee undertook an aggressive campaign of publishing, lobbying, and public speaking, and Clarkson himself spent much time traveling the country, both gathering intelligence about the workings of the slave trade and giving speeches against its evils. Government took notice, and some time in 1787 or 1788 the Ministry ordered one Captain Parrey of the Royal Navy to conduct a detailed survey of the slave ships docked at Liverpool, with an eye toward determining the actual conditions to which enslaved persons were subject on the trans-Atlantic passage.

Parrey’s findings were so shocking that the Society chose to let the facts speak for themselves, beginning a publishing campaign that would change the world. The Society’s members issued a torrent of pamphlets, but also in November 1788 the Plymouth Committee issued “Plan of an African Ship’s Lower Deck with Negroes in the Proportion of Only One to a Ton”, a simple image showing hundreds of enslaved persons crammed into the lower deck of an unnamed vessel.

This impact of the image was so powerful that it was adapted, revised, expanded and reissued by the Society. To make concrete the cruelty of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, the broadside uses as a representative example the slave ship Brooks, constructed in 1781 and one of the Liverpool vessels surveyed by Parrey in 1788.

The text begins by describing in minute detail the dimensions of the Brooks’ decks, then explaining how 602 enslaved Africans were crammed in on one particular voyage—though the Brooks was nominally designed to hold “just” 452. The 351 men were for example nominally allotted six feet by one foot four inches each, but by being forced to lie on their sides could be compressed to six feet by nine or ten inches each (not a typo), in a space so low that sitting upright was impossible. The amazing thing is, all this information seems to have been provided by the slave merchants themselves.

These statistics are amply illustrated by the copperplate engraving at left, which offers three cross-sections and four plan views of the Brooks. It’s the plan views that are the most shocking, in particular the one at bottom, showing several hundred persons crammed on the 100 by 25 foot lower deck.

The text goes on to describe slavers’ methods of securing the men (to prevent “insurrections”); feeding, exercising, and “caring” for their human cargo; and the catastrophic levels of mortality. It then tackles a favorite argument of those engaged in the slave trade, namely that it “the suppression of it will destroy a great nursery for seamen”, quoting Clarkson to the effect that “in this traffick only, a greater proportion of men perish in ONE year, than of all the other trades of Great Britain in TWO years.” The broadside ends with a ringing call to action:

“As then the inhumanity of this trade must be universally admitted and lamented, people would do well to consider that it does not often fall to the lot of individuals, to have an opportunity of performing so important a moral and religious duty, as that of endeavouring to put an end to a practice, which may, without exaggeration, be stiled one of the greatest evils at this day existing upon the earth.”

The broadside and its variants were a sensation. Indeed, according to the British Museum, it “so impressed Mirabeau in Paris that he had a wooden model (51 x 12 cm) made from it which survives in the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal”. The images and text—particularly the image of the lower deck—were endlessly adapted and reprinted—both in Great Britain and the United States, one of the first appearances here being in 1789 in Matthew Carey’s American Museum.

The movement toward abolition of the slave trade stalled in the 1790s, perhaps because the British government was consumed by the wars with Revolutionary and Napoleonic France. Likewise, the violent, interconnected excesses of the French and Haitian Revolutions, both of which had embraced the abolition of slavery altogether, may well have given pause to would-be abolitionists in Britain. Nevertheless, in early 1807 Parliament overwhelmingly approved James Wilberforce’s bill to abolish the slave trade, though not the practice of slavery itself.

Parry was sent to report on slave ships in the wake of the Slave Trade Act of 1788, the first English law regulating the trade, which limited the number of slaves per ship. Parry states by following the plans, the ship (the Brooks) should carry 482 men, women and children, but actually carried 609. The last sentence concludes that is a moral and religious duty to end 'one of the greatest evils at this day existing upon the earth'.

This version was published in '”An Essay on Colonisation Particularly Applied to the Western Coast of Africa'”, by Swedish abolitionist Carl Bernhard Wadstrom (1746-99). In this work he argued that a colony would profit more from trade with the locals than exploited them as slaves.

Join our mailing list

* denotes required fields

We will process the personal data you have supplied in accordance with our privacy policy (available on request). You can unsubscribe or change your preferences at any time by clicking the link in our emails.